Matrix Operations: Perspective

In the last post, we looked into the matrix math you can use to move and rotate objects in your 3D game. Now we only need to, erm, put things into perspective.

This is the fifth post in a series about recreating the Stunt Car Racer game for modern platforms. You can find the previous posts by looking the Stunt Car Racer tag. A very quick recap: We have some existing C++ code which uses the Direct3D API to render the graphics, but since that is Windows-specific, we want to convert it to OpenGL. This involves understanding some of the matrix math going on, since it works slightly differently in Direct3D and OpenGL - the order of matrix multiplications are switched around, and some of the coordinate systems are a bit different.

You may want to read the last post before diving into this one, as it lays the foundation of using matrix math to transform 3D objects around. As in the previous post, the math shown will be for a 2D game that gets projected on a 1D screen, but it is easy to generalize this to a 3D game that gets projected on a 2D screen.

Reading time: 10 minutes

The Vertex Shader

Just to recap a tiny bit, our vertex shader looks something like this:

attribute vec3 vPosition;

uniform mat4 projectionMatrix;

uniform mat4 viewMatrix;

uniform mat4 worldMatrix;

void main() {

gl_Position = vPosition * worldMatrix * viewMatrix * projectionMatrix;

}

We already know what to supply as worldMatrix and viewMatrix, and we understand that OpenGL is

able to take an array of 3D points and, in a massively parallel way, run our vertex shader on every

one of these 3D points, yielding another set of (transformed) 3D points. vPosition in the vertex

shader is a single input point, and gl_Position is the output point.

But we still don’t know what to supply as projectionMatrix.

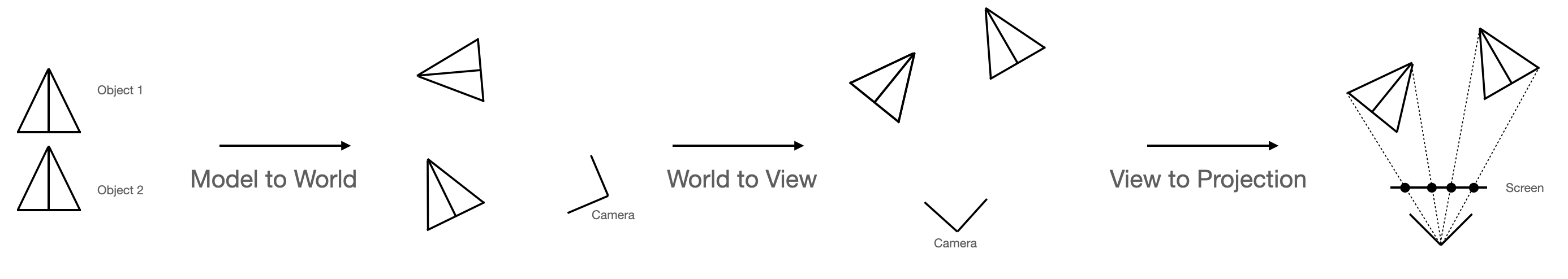

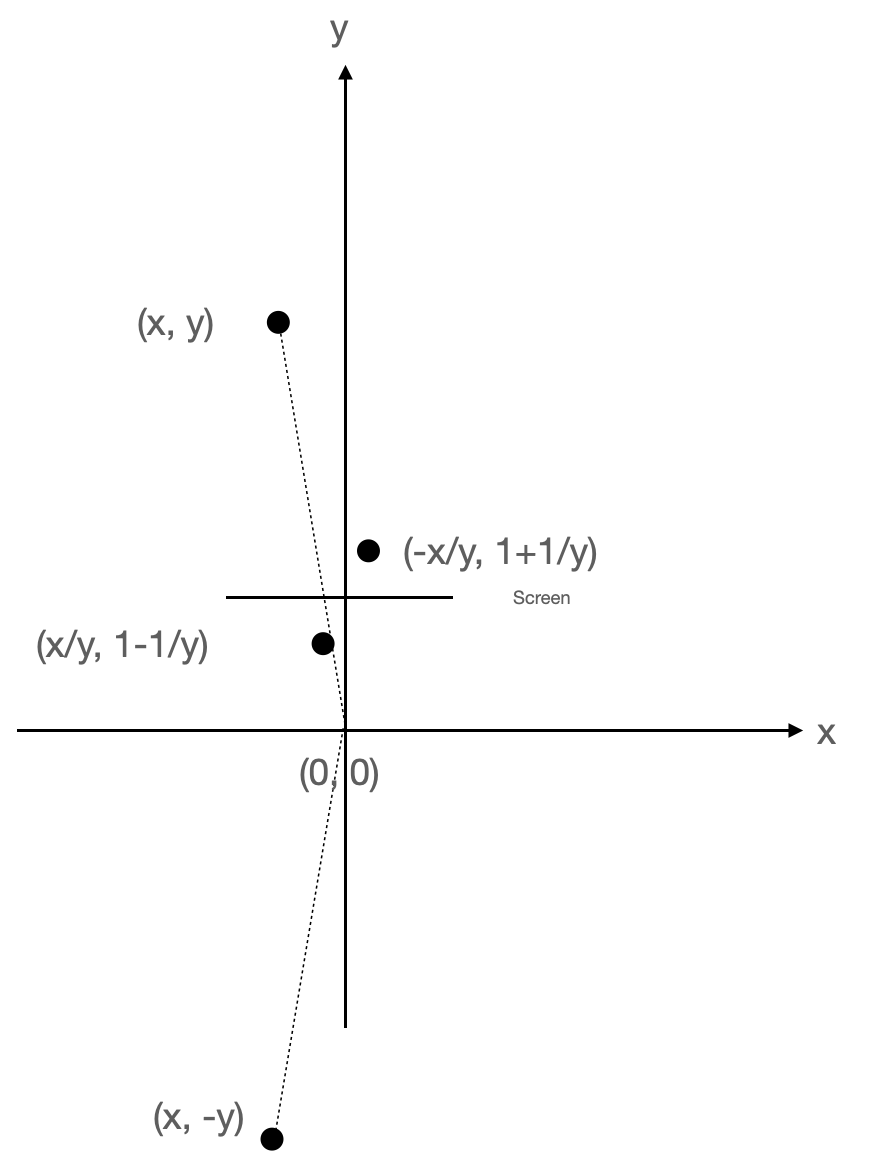

Let’s have a look at a figure from the previous post: worldMatrix and viewMatrix move our 3D

models around so that the camera can be at a well-defined position and face in a well-defined

direction. Then projectionMatrix does some math to project the 3D world to our 2D screen - here

shown as projecting a 2D world down to a 1D screen:

Division by Matrix Multiplication

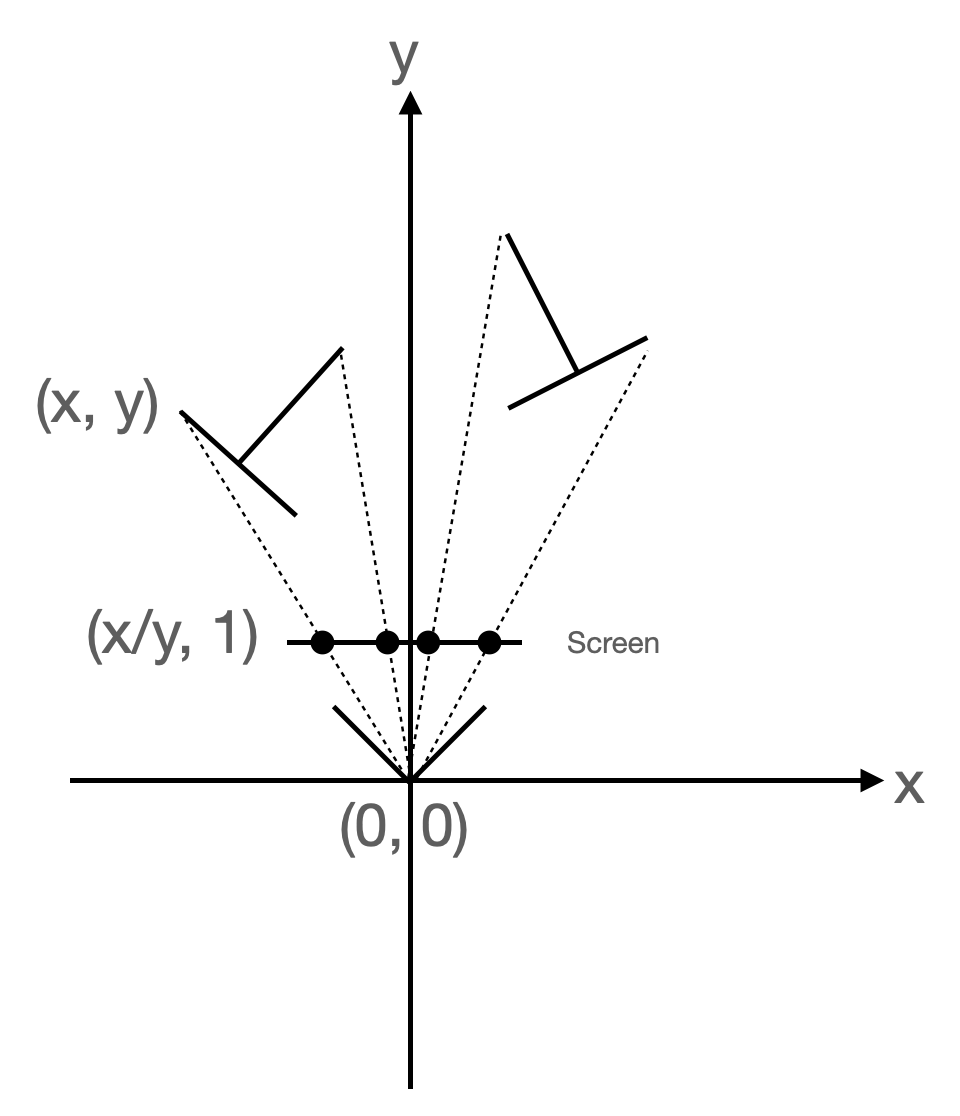

As you may have guessed, in order to make distances far away from the camera look smaller on the screen than

distances close to the camera, what we really need to do is divide the coordinates with the distances to the

points. Again, assuming that instead of a 3D game and a 2D screen we have a 2D game and a 1D screen, we need

to divide the coordinates by the y component:

(The thing pointing out from (0, 0) represents the camera 😬…)

This sounds easy! We just make up a 3x3 matrix that, when multiplied with a 3-dimensional vector, divides everything in the vector by the vector’s 2nd component. However, let’s also recap how multiplication of a vector and a matrix works:

(Sorry, you may need to scroll the formula in order to see all of it…)

Hmmm, it doesn’t look like there’s any way to divide by y, right…?

Solution: Redefine what a vector is!

Enter the world of homogenous coordinates!

This was completely new to me, and it solves our issue. So far, in all of our calculations,

the last component of our vectors has been set to 1, and our rotation and translation matrices

are defined such that they leave that last vector component at the same value.

But what if we add some meaning to the last component of our vectors? That’s what homogenous coordinates

do. The idea is a bit weird at first: Two vectors a and b are considered the same if you get the

same coordinates by dividing by the value of the last coordinate. So the vector

and

are the same when considered as homogenous coordinates, since

If we buy into this idea, we can divide x by y by multiplying z by y and leaving x

as-is:

This probably also means our vertex shader has to know about homogenous coordinates:

attribute vec3 vPosition;

uniform mat4 projectionMatrix;

uniform mat4 viewMatrix;

uniform mat4 worldMatrix;

void main() {

vec4 homogenousPosition = vec4(vPosition.x, vPosition.y, vPosition.z, 1.0);

vec3 transformedPosition = homogenousPosition * worldMatrix * viewMatrix * projectionMatrix;

gl_Position = transformedPosition / transformedPosition.w;

}

Not too bad. But exactly which matrix can we use to multiply the last component of a vector with the next-to-last-component? Try this:

We did it!

Adding Depth Information

This is really great, but before a framework like OpenGL can render all of our graphics correctly, it also needs to know how far away from the camera the individual elements are, so that objects far from the camera do not get painted over objects close to the camera. In other words, we need to preserve some depth information.

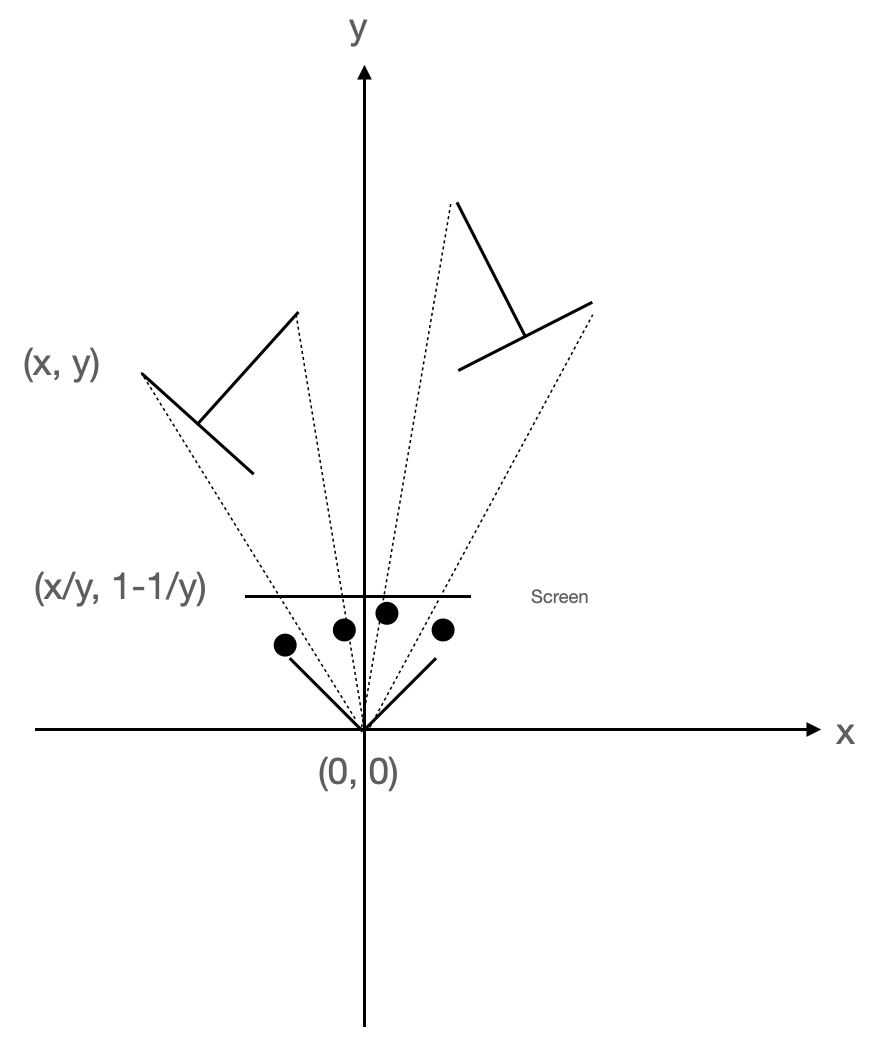

Let’s tweak our matrix a tiny, tiny bit:

This seems to work: The bigger the initial y value is, the bigger 1-1/y is, so we keep some

depth information:

Of course, in real life your perspective matrix will not be quite as simple as the one above: Your 2D screen is typically a bit wider than it is tall, so you will want to accommodate for that. But we now have the right idea, and the rest is (duck!) implementation details.

Now, talking about implementation details…

Back to Stunt Car Racer

It took me a while to get to the idea of homogenous coordinates, and as noted previously there are other differences between Direct3D and OpenGL (the “viewing frustums” are different, and various coordinate systems are upside-down), but finally I got the vertex shader to do the right thing. I thought. It looked fine when the camera was in the air, looking down on a track, but once you selected a track and viewed a car racing around that track - the camera hovering just above the track - something really weird happened:

Whoa! Everything looked totally garbled. And yet… it looked like the right stuff was being painted, but then another part of the track was being painted upside-down on top of everything as well. Interesting. Why?

Watch Your Back

In all my excitement about homogenous coordinates, I had only considered points in front of the

camera. But what happens with points behind the camera? They also go through our vertex shader, and

it turns out that they turn into points in front of the camera after the math in the shader. You

know, -y / -y is the same as y / y, namely 1. So you get this:

I started by changing the vertex shader to just remove points behind the camera. This worked OK, but led to some aggressive “clipping”: The parts of the track closest to the camera would be removed a bit too early, since parts of it would be behind the camera and other parts would still be in front:

(Also, the rotation matrices were not exactly in place at this time, which is why the track seems to bounce in a weird way…)

Eventually, though, I found out that OpenGL knows about homogenous coordinates, so all of my changes to the vertex shader had been a wasted effort. By going back to something resembling the first version above, and spending a lot of time getting the view frustum right, it finally started to look the way it should:

Conclusion

Although this and the previous post don’t show you the exact matrices you will need to use for a 3D game, I hope they have given you an idea of how matrix multiplication can be used to move around objects in your game and make everything look right on the player’s screen. It’s a lot of math, and not all of it is super intuitive at first, but I think it is important to have a basic understanding of how it all fits together. For me, at least, that removes some of the anxiety I have previously had when doing 3D games with various graphics libraries.

As always, you can try out the current version of the actual game from your browser (currently only supported on desktop computers).